If you have picked up one of our seed packets, we have provided you with enough seed mixture to cover an area of 1 metre squared. Follow this step by step guide to creating your very own patch of wildflowers…..the bees will thank you for it!!

To increase your chances of establishing a successful wildflower meadow, it is highly recommended that you sow in Early Spring (March/April).

Step 1: Choose somewhere to create your patch. Ideally you need to have a bit of bare ground that gets plenty of sunshine throughout the day, isn’t too fertile and isn’t too weedy. Wildflowers LOVE poor soils that most other plants wouldn’t dream of growing in! Mark out the outline of a 1M squared area using sand, an old hose pipe or some twine/string.

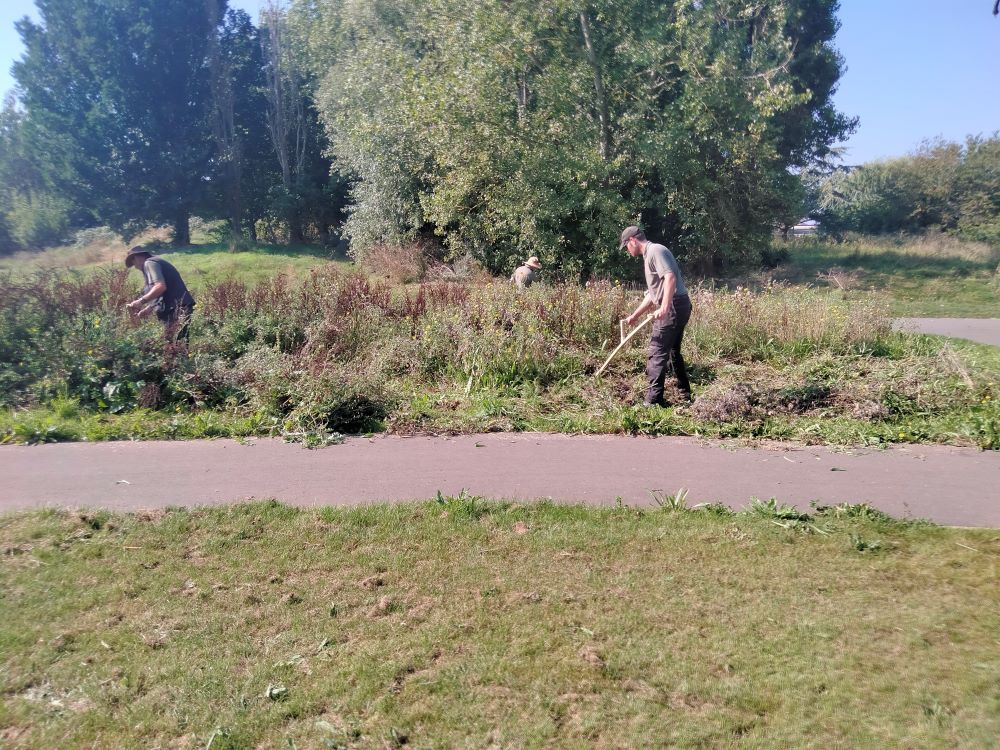

Step 2: If your chosen patch of ground is grassy, it is best to remove the grass beforehand. Grab your shovel and gradually lift the grass and any weeds from your patch, try not to leave any behind to rot down as this can risk returning extra nutrients back to the soil. Remember…. wildflowers love poor soil!

Step 3: When you have a bare patch of ground, dig it over with a garden fork and rake the soil level and to a fine crumbly texture. Then with your wellies on, tread over the ground to firm up the surface.

Step 4: Split the contents of your seed packet in half and mix one half with some fine dry sand (Roughly 1 part seed to 2 parts sand). This helps you see where you are spreading the seed more clearly. Using a tablespoon, scatter the seed and sand mixture over half the patch. Repeat this with the remaining seed, covering the other half of your patch.

Step 5: Tread all over the area again to ensure good contact between the seed mix and the soil, there is no need to rake it in or to cover the seed with soil. Give your newly sown seeds a good shower of water with your watering can. Remember to water regularly in dry weather!

Step 6….Wait for nature to do its thing! Ensure that your patch is well watered as it gets established. Don’t be discouraged if your patch doesn’t suddenly burst into life! It takes a little while for the flowers and grasses to germinate and get going so don’t give up! It will get better with each year. As and when perennial weeds pop up, such as dandelion, dock etc, you can dig these out by hand to give your wildflower seedlings a better chance.

Maintaining your Wildflower Meadow

Year 1

In the first year of sowing, it may take a little while for your wildflowers and grasses to get going. This is perfectly normal and is because most are perennial, that is they come back year after year, and can be slow to establish and some won’t even flower in the first year! What you might see however is some of the existing annual weeds which have laid dormant in the soil come through. This can shade out your meadow seedlings and an easy way to remedy this is to either chop back the weedy growth with shears or mow over your patch. Mowing may sound drastic but it’s quite important in the first year, you should aim to mow or cut back growth in your patch regularly to around 40mm to 60mm. Be sure to remove the cuttings- these can be composted! Doing this ensures that annual weeds are kept under control and provides your slower developing species with time to catch up with fast growers!

Year 2 and onwards

Your meadow should be left to develop from spring into late summer to allow it to flower and provide pollinators with a rich habitat and source of food. In Late July or August, after your meadow has flowered you should take what’s traditionally known as a “hay cut”. Cut back your meadow to around 50mm and leave the cuttings, also known as “arisings”, to dry out and shed seed on your patch, this takes up to 7 days. After which you can remove the arisings and pop them in your compost. Any regrowth can be cut back again in late autumn and in the following spring if needed.

The seed mix that we have provided was kindly donated by West Sussex County Council. It is a general mix of flowers and grasses developed by Emorsgate Seeds that can be used on various soil types.

Some of the species that might pop up in your patch are as follows:

Wild Flowers: Yarrow, Agrimony, Kidney Vetch, Betony, Common Knapweed, Greater Knapweed, Wild Carrot, Hedge Bedstraw, Meadow Crane’s-bill, Field Scabious, Oxeye Daisy, Birdsfoot Trefoil, Black Medick, Wild Marjoram, Wild Parsnip, Salad Burnet, Cowslip, Selfheal, Meadow Buttercup, Common Sorrel, Pepper Saxifrage, Bladder Campion, Upright Hedge-parsley, Tufted Vetch.

Wild Grasses: Common Bent, Crested Dogstail, Red Fescue, Smaller Cat’s-tail, Smooth-stalked Meadow-grass.

We would love to see photographs of your wildflower patch, please send them in to thewildflowertrail@gmail.com so that we can share them on the trail website (please ensure proper consent).